“The blood of the Zimmi

is like the blood of the Moslem”—ALI.

HITHERTO, we have

considered the teachings of the Arabian Prophet solely from one point of

view—as furnishing the rule of human conduct, and supplying the guide of man’s

duty to his Creator and to his fellow- creatures. We now propose to examine the

influence of Islam on collective humanity—on nations, and not merely on the

individual, in short, on the destiny of mankind in the aggregate.

Seven centuries

had passed since the Master of Nazareth had come with his message of the

Kingdom of Heaven to the poor and the lowly. A beautiful life was ended before

the ministry had barely commenced. And now unutterable desolation brooded over

the empires and kingdoms of the earth, and God’s children, sunk in misery, were

anxiously waiting for the promised deliverance which was so long in coming.

In the West, as in

the East, the condition of the masses was so miserable as to defy description.

They possessed no civil rights or political privileges. These were the monopoly

of the rich and the powerful, or of the sacerdotal classes. The law was not the same for the weak and the

strong, the rich and the poor, the great and the lowly. In Sasanide Persia, the

priests and the landed proprietors, the Dehkâns, enjoyed all

power and influence, and the wealth of the country was centred in their hands.

The peasantry and the poorer classes generally were ground to the earth under a

lawless despotism. In the Byzantine Empire, the clergy and the great magnates,

courtezans, and other nameless ministrants to the vices of Cæsar and proconsul, were the happy possessors of

wealth, influence and power. The people grovelled in the most abject misery. In

the barbaric kingdoms—in fact, wherever feudalism had established itself— by

far the largest proportion of the population were either serfs or slaves.

Villeinage or

serfdom was the ordinary status of the peasantry. At first there was little

distinction between prædial and domestic

slavery. Both classes of slaves, with their families, and their goods and

chattels, belonged to the lord of the soil, who could deal with them at his own

free will and pleasure. (1) In later times the serfs or villeins were either

annexed to the manor, and were bought and sold with the land to which they

belonged, or were annexed to the person of the lord, and were transferable from

one owner to another. They could not leave their lord without his permission;

and if they ran away, or were purloined from him, might be claimed and

recovered by action, like beasts or other chattels. They held, indeed, small

portions of land by way of sustaining themselves and their families, but it was

at the mere will of the lord, who might dispossess them whenever he pleased. A

villein could acquire no property, either in land or goods; but if he purchased

either, the lord might enter upon them, oust the villein, and seize them to his

own use.

An

iron collar round the neck was the badge of both prædial servitude and

domestic slavery. The slaves were driven from place to place in gangs, fed like

swine, and housed worse than swine, with fettered feet and manacled hands,

linked together in a single chain which led from collar to collar. The trader

in human flesh rode with a heavy knotted lash in his hands, with which he

‘encouraged’ the weary and flagging. This whip when it struck, and that was

frequently, cut the flesh out of the body. Men, women, and children were thus

dragged about the country with rags on their body, their ankles ulcerated,

their naked feet torn. If any of the wretches flagged and fell, they were laid

on the ground and lashed until the skin was flayed and they were nearly dead.

The horrors of the Middle Passage, the sufferings of the poor negroes in the Southern States of North America before

the War of Emancipation, the cruelties practised by the Soudanese

slave-lifters, give us some conception of the terrible sufferings of the slaves

under Christian domination at the time when Islam was first promulgated, and until

the close of the fifteenth century.

(2) And even after the lapse of

almost two thousand years of Christ’s reign, we still find Christians lashing to death helpless women, imprisoned for real or imaginary

political offences by one of the most powerful empires of the

civilised world. (3)

The condition of the so-called freemen was nowise better than

that of the ordinary serfs. If they wanted to part with their lands, they

must pay a fine to the lord of the manor. If

they wanted to buy any, they must likewise pay a fine. They could not take by

succession any property

until they had paid a heavy

duty. They could not grind their corn

or make their bread without paying a share to the lord. They could not harvest their

crops before the Church had first appropriated its tenth, the king his twentieth, the courtiers their smaller shares. They could

not leave their homes without the leave

of the lord, and they were bound, at

all times, to render him gratuitous services.

If the lord’s son or daughter married, they must cheerfully pay their

contributions. But when the freeman’s

daughter married, she must first

submit to an infamous outrage —and

not even the bishop, the servant of Christ, when he happened to be the lord of the manor, would waive the atrocious privilege of barbarism. Death even had no solace for these poor victims of barbarism. Living, they were subject to the

inhumanities of man; dead, they were

doomed to eternal perdition; for a felo-de-se

was the unholiest of criminals, there was no room for his poor body in

consecrated ground; he could

only be smuggled away in the dead of night and buried in

some unhallowed spot with a stake through his body as a warning to others.

Such, was the

terrible misery which hung over the people! But the baron in his hall, the

bishop in his palace, the priest in his cloister, little recked they of the

sufferings of the masses. The clouds of night had gathered over the fairest

portion of Europe and Africa. Everywhere the will of the strongest was the

measure of law and right. The Church afforded no help to the downtrodden and

oppressed. Its teachings were opposed to the enfranchisement of the human race

from the rule of brute force. “The early Fathers” had condemned resistance to

the constituted authorities as a deadly sin. No tyranny, no oppression, no

outrages upon humanity were held to justify subjects in forcibly protecting

themselves against the injustice of their rulers. The servants of Jesus had

made common cause with those whom he had denounced, —the rich and powerful

tyrant. They had associated themselves with feudalism, and enjoyed all its

privileges as lords of the soil, barons and princes.

The

non-Christians—Jews, heretics, or pagans—enjoyed, under Christian domination, a

fitful existence. It was a matter of chance whether they would be massacred or

reduced to slavery. Rights they had none; enough if they were suffered to

exist. If a Christian contracted an illicit union with a non-Christian, —a

lawful union was out of the question, —he was burnt to death. The Jews might

not eat or drink or sit at the same table with the Christians, nor dress like

them. Their children were liable to be torn from their arms, their goods

plundered, at the will of the baron or bishop, or a frenzied populace. And this

state of things lasted until the close of the seventeenth century.

Not until the

Recluse of Hira sounded the note of freedom, —not until he proclaimed the

practical equality of mankind, not until he abolished every privilege of caste,

and emancipated labour, —did the chains which had held in bond the nations of

the earth fall to pieces. He came with the same message which had been brought

by his precursors and he fulfilled it.

The essence of the

political character of Islâm is to be found

in the charter, which was granted to the Jews by the Prophet after his arrival

in Medina, and the notable message sent to the Christians of Najrân and the neighbouring territories after Islâm had fully established itself in the Peninsula. This

latter document has, for the most part, furnished the guiding principle to all

Moslem rulers in their mode of dealing with their non-Moslem subjects and if

they have departed from it in any instance the cause is to be found in the

character of the particular sovereign. If we separate the political necessity

which has often spoken and acted in the name of religion, no faith is more

tolerant than Islâm to the followers

of other creeds. (4) “Reasons of State” have led a sovereign here and there to

display a certain degree of intolerance, or to insist upon a certain uniformity

of faith; but the system itself has ever maintained the most complete

tolerance. Christians and Jews, as a rule, have never been molested in the

exercise of their religion, or constrained to change their faith. If they are

required to pay a special tax, it is in lieu of military service, and it is but

right that those who enjoy the protection of the State should contribute in

some shape to the public burdens. Towards the idolaters there was greater

strictness in theory, but in practice the law was equally liberal. If at any

time they were treated with harshness, the cause is to be found in the passions

of the ruler or the population. The religious element was used only as a

pretext.

In support of the

time-worn thesis that the non-Moslem subjects (5) of Islâmic States labour under severe disabilities, reference

is made not only to the narrow views of the later canonists and lawyers of Islâm, but also to certain verses of the Koran, in order

to show that the Prophet did not view non-Moslems with favour, and did not

encourage friendly relations between them and his followers. (6) In dealing

with this subject, we must not forget the stress and strain of the

life-and-death struggle in which Islâm was involved

when those verses were promulgated, and the treacherous means that were often

employed by the heathens, as well as the Jews and the Christians, to corrupt

and seduce the Moslems from the new Faith. At such a time, it was incumbent

upon the Teacher to warn his followers against the wiles and insidious designs

of hostile creeds. And no student of comparative history can blame him for

trying to safeguard his little commonwealth against the treachery of enemies

and aliens. But when we come to look at his general treatment of non-Moslem

subjects, we find it marked by a large-hearted tolerance and sympathy.

Has any conquering

race or Faith given to its subject nationalities a better guarantee than is to

be found in the following words of the Prophet? “ To [the Christians of] Najrân and the neighbouring territories, the security of

God and the pledge of His Prophet are extended for their lives, their religion,

and their property—to the present as well as the absent and others besides;

there shall be no interference with [the practice of] their faith or their

observances; nor any change in their rights or privileges : no bishop shall be

removed from his bishopric; nor any monk from his monastery, nor any priest

from his priesthood, and they shall continue to enjoy every thing great And

small as heretofore; no image or cross shall be destroyed; they shall not

oppress or be oppressed ; they shall not practise the rights of blood-vengeance

as in the Days of Ignorance; no tithes shall be levied from them nor shall they

be required to furnish provisions for the troops.” (7)

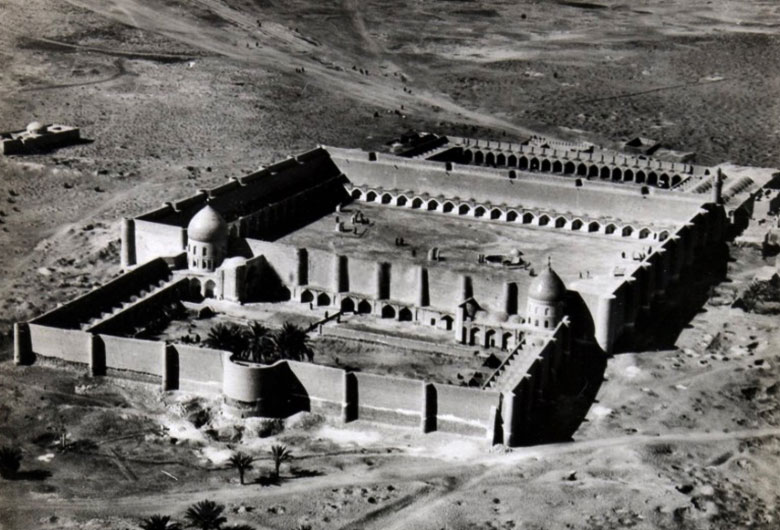

After the

subjugation of Hira, and as soon as the people had taken the oath of

allegiance, Khâlid bin-Walid

issued a proclamation by which he guaranteed the lives, liberty and property of

the Christians, and declared that “they shall not be prevented from beating

their nâkus (8) and taking out their

crosses on occasions of festivals.” “And this declaration,” says Imâm Abu-Yusuf, (9) “was approved of and sanctioned by

the Caliph (10) and his council.” (11) The non-Moslem subjects were not

precluded from building new churches or temples. Only in places exclusively

inhabited by Moslems a rule of this kind existed in theory. “No new Church or

temple,” said Abdullah bin Abbâs, (12) “can be

erected in a town solely inhabited by Moslems; but in other places where there

are already Zimmis inhabiting from before, we must abide by our contract

with them.” (13) In practice, however, the prohibition was totally disregarded.

In the reign of Mâmùn, we hear of eleven thousand Christian churches,

besides hundreds of synagogues and fire-temples within the empire. This

enlightened monarch, who has been represented as “a bitter enemy” of the

Christians, included in his Council the representatives of all the communities

under his sway, — Moslems, Jews, Christians, Sabæans

and Zoroastrians; whilst the rights and privileges of the Christian hierarchy

were carefully regulated and guaranteed.

It is a notable

fact, with few parallels even in modern history, that after the conquest of

Egypt the Caliph Omar scrupulously preserved intact the property dedicated to

the Christian churches and continued the allowances made by the former

government for the support of the priests. (14)

The best testimony

to the toleration of the early Moslem government is furnished by the Christians

themselves. In the reign of Osmân (the third

Caliph), the Christian Patriarch of Merv addressed the Bishop of Fars, named

Simeon, in the following terms: The Arabs who have been given by God the

kingdom (of the earth) do not attack the Christian faith ; on the contrary they

help us in our religion; they respect our God and our Saints, and bestow gifts

on our churches and monasteries.”

In order to avoid

the least semblance of high-handedness, no Moslem was allowed to acquire the

land of a zimmi even by purchase. “Neither the Imàm nor the Sultan could dispossess a zimmi of

his property.”

The Moslems and

the zimmis were absolutely equal in the eve of the law. “Their blood,”

said Ali the Caliph, “was like our blood.” Many modern governments, not

excepting some of the most civilised, may take the Moslem administration for

their model. In the punishment of crimes there was no difference between the

rulers and the ruled. Islam’s law is that if a zimmi is killed by a

Moslem, the latter is liable to the same penalty as in the reverse case. (15)

In their anxiety

for the welfare of the non-Moslem subjects, the Caliphs of Bagdad, like their

rivals of Cordova, created a special department charged with the protection of

the zimmis and the safeguarding of their interests. The head of this

department was called, in Bagdad, Katib-ul-Jihbazeh, in Spain, Katib-uz-Zimam.

(16)

Mutawakkil, who

rased to the ground the mausoleum of the martyr Husain and forbade pilgrimages

to the consecrated spot, excluded non-Moslems, as he excluded the Moslem

Rationalists, from the employment of the State and subjected them to many

disabilities. In the later works

of law, written whilst the great struggle was proceeding between Islam and

Christendom, on one side for life, on the other for brute mastery, there occur

no doubt passages which give colour to the allegation that in Islam zimmis

are subject to humiliation. But no warrant for this statement will be found in

the rules inculcated by the Teacher, or his immediate disciples or successors.

It must be added, however, that the bigoted views of the later canonists were

never carried into practice; and the toleration and generosity with which the

non-Moslems were Created are evidenced by the fact that zimmis could be

nominated as executors to the wills of Moslems; that they often filled the

office of rectors of Moslem universities and educational institutions, and of

curators of Moslem endowments so long as they did not perform any religious

functions. And when a non-Moslem of worth and merit died, the Moslems attended

his funeral in a body.

In the beginning

military commands, for obvious reasons, were not entrusted to non-Moslems, but

all other posts of emolument and trust were open to them equally with Moslems.

This equality was not merely theoretical, for from the first century of the

Hegira we find important offices of state held by Christians, Jews and Magians.

The Abbasides, with rare exceptions, recognised no distinction among their

subjects on the score of religion. And the dynasties that succeeded them in

power scrupulously followed their example.

If the treatment

of non-Moslems in Islamic countries is compared with that of non-Christians

under European Governments, it would be found that the balance of humanity and

generosity, generally speaking, inclines in favour of Islam. Under the Mogul

Emperors of Delhi, Hindus commanded armies, administered provinces and sat in

the councils of the sovereign. Even at the present time can it be said that in

no European empire, ruling over mixed nationalities and faiths, is any

distinction made of creed, colour or race?

That which Islam

had almost exclusively in view was to inculcate among mankind the principle of

divine unity and human equality preached by the Prophet. So long as the central

doctrine of the unity of God and the message of the Prophet is recognised and

accepted, Islam allows the widest latitude to the human conscience.

Consequently, wherever the Moslem missionary-soldier made his appearance, he

was hailed by the down-trodden masses and the persecuted heretics as the

harbinger of freedom and emancipation from a galling bondage. Islam brought to

them practical equality in the eye of the law, and fixity or taxation.

The battle of

Kadesia, which threw Persia into the hands of the Moslems, was the signal of

deliverance to the bulk of the Persians, as the battles of Yermuk and Ajnâdin were to the Syrians, the Greeks, and the

Egyptians. The Jews whom the Zoroastrians had massacred from time to time, the

Christians, whom they hunted from place to place, breathed freely under the

authority of the Prophet, the watchword of whose faith was the brotherhood of

man. The people everywhere received the Moslems as their liberators. Wherever

any resistance was offered, it was by the priesthood and the aristocracy. The

masses and the working classes in general, who were under the ban of

Zoroastrianism, ranged themselves with the conquerors. A simple confession of

an everlasting truth placed them on the same footing as their Moslem

emancipators.

The feudal chiefs

of the tribes and pillages retained all their privileges, honours, and local

influence, — “more than we believe,” says Gobineau, “for the oppressions and

persecutions of the Musulmans have been greatly exaggerated.”

The conquest of

Africa and Spain was attended with the same result. The Arrans, the Pelagians,

and other heretics hitherto the victims of orthodox fury and hatred, —the

people at large, who had been terribly oppressed by a lawless soldiery and a

still more lawless priesthood, —found peace and security under Islam. By an

irony of fate, which almost induces a belief in the Nemesis of the ancients,

the Jews, whose animosity towards the Prophet very nearly wrought the

destruction of the Islamic commonwealth, found in the Moslems their best

protectors. “Insulted, plundered, hated and despised by all Christian nations,”

they found that refuge in Islam, that protection from inhumanity, which was

ruthlessly denied to them in Christendom.

Islam gave to the

people a code which, however archaic in its simplicity, was capable of the

greatest development in accordance with the progress of material civilisation.

It conferred on the State a flexible constitution, based on a just appreciation

of human rights and human duty. It limited taxation, it made men equal in the

eye of the law, it consecrated the principles of self-government. It

established a control over the sovereign power by rendering the executive

authority subordinate to the law, —a law based upon religious sanction and

moral obligations. “The excellence and effectiveness of each of these

principles,” says Urquhart “(each capable of immortalising its founder), gave

value to the rest; and all combined, endowed the system which they formed with

a force and energy exceeding those of any other political system. Within the

lifetime of a man, though in the hands of a population, wild, ignorant, and

insignificant, it spread over a greater extent than the dominions of Rome.

While it retained its primitive character, it was irresistible.” (17) The short

government of Abu Bakr was too fully occupied with the labour of pacifying the

desert tribes to afford time for any systematic regulation of the provinces.

But with the reign of Omar —a truly great man —commenced that sleepless care

for the welfare of the subject nations which characterised the early Moslem

governments.

An examination of

the political condition of the Moslems under the early Caliphs brings into view

a popular government administered by an elective chief with limited powers. The

prerogatives of the head of the State were confined to administrative and

executive matters, such as the regulation of the police, control or the army,

transaction of foreign affairs, disbursement of the finances, etc. But he could

never act in contravention of the recognised law.

The tribunals were

not dependent on the government. Their decisions were supreme; and the early

Caliphs could not assume the power of pardoning those whom the regular

tribunals had condemned. The law was the same for the poor as for the rich, for

the man in power as for the labourer in the field.

References: 1) The Church retained its slaves longest. Sir Thomas Smith in his Commonwealth speaks bitterly of the hypocrisy of the clergy. 2) In the Parliamentary War both sides sold their opponents as slaves to the colonists. Alter the suppression of the Duke of Monmouth's rebellion all his followers were sold into slavery. The treatment of the slaves in the colonies at the hands of “the Pilgrim Fathers” and their descendants will not bear description. 3) This was written before the fall of the Romanoffs 4) Comp. Gobineau, Les Religions et les Philosophies dans l’Asie Conirals 5) In the Islamic system the non-Moslem eubjects of Moslem States are called Ahl-ux-zimma or zimmis, i.e “people living under guarantees.” 6) See Sell’s Essays on Islam 7) I.e. nor shall troops be quartered on them: Futuh ul-Buldan (Balazuri). p. 65; Kitab ul-Kharaj of Imam Abu Yusuf. Muir gives this guarantee of the Prophet in an abridged form, vol. ii. P. 299; see Appendix. 8) A piece of wood used in Eastern Christian churches in place of a be1l. 9) The Chief Kazi of Harun ar-Rashid. 10) Abu Bakr. 11) Consisting of Omar. Osman and Ali and the other leading Companions of the Prophet: see the Kitab ul-Kharaj, p. 84. 12) A cousin of the Prophet and a jurist of recognised authority. 13) Kitab ul-Kharaj, p 88 14) Makrizi, pp. 492, 499 15) Zail in his Takhrij-ul-Hedaya yr mentions a case which occurred in the Caliphate of Omar. A Moslem of the name of the name of Bakr bin Wail killed a Christian named Hairut. The Caliph ordered that “the killer should be surrendered to the heirs of the killed”. The culprit was made over to Honain, Hairut’s heir, who put him to death, p. 338, Delhi edition. A similar case is reported in the reign of Omar bin Abdul Aziz. 16) With a Zal; see The Short History of the Saracens, p. 573. 17) Urquhart, Spirit of the East, vol. i. Introd. p. xxviii.

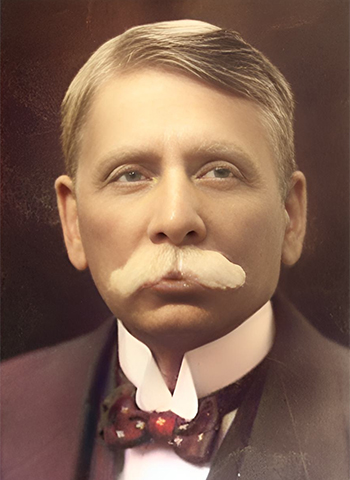

Syed Ameer Ali

Syed Ameer Ali (1849–1928) was a renowned Muslim thinker, historian, and jurist. He significantly contributed to the Muslim renaissance in British India and was the first Muslim judge at the Calcutta High Court. His works, “The Spirit of Islam" and “A Short History of the Saracens" are key texts on Islamic history. Syed Ameer Ali was a strong advocate for the modernization of Muslim society of Indian Subcontinent.

আরো পড়ুন